Introduction

For a long time, Google search is being used by hackers to find specific elements on web applications by building customized queries containing advanced search operators. Using search results to identify security flaws is known as Google Dorks. This concept was introduced in 2002 by a computer security expert, Johnny Long, while Using Google as a Security Testing Tool[1].

Searching site:net inurl:”intro.asp” results in a list of domains ending in .net and URL containing intro.asp. Crafting and executing a search of an effective term (or dork) respecting the syntax may lead to results that lie in range of security issues such as sensitive information disclosure, SQL injection points, cross-site scripting, file inclusion and sometimes uploaded backdoors. As demonstrated in Long’s presentation[2] it is also possible to find error messages with a certain level of verbosity, backup archives and diverse types of documents.

Taking advantage of big internet data collection for intelligence purposes (OSINT) can fall in a less ethical category as described in [3] since most of the times this type of information is handled directly. The main purpose of this research is not focusing on common well-known dorks but to explore new ways of constructing search terms that lead to yet unexplored results.

Detecting unusual keywords

A few wild bytes appeared while testing a program feature under WineHQ environment due to memory leak. These bytes were printed as CJK characters because of encoding. For curiosity’s sake, some searches (and translations) were performed to check if spitted out text had something meaningful. A fair example is string 섁䢃쀁衐/똑蓒痥ᅦ䐤ࠁé䷲. When searched, returns a lot of binary files, documents and images. There is a high chance of finding web applications vulnerable to path traversal given how often these files are usually included. Note that results may vary according to your session and location.

Turns out some strings would translate to https://eur-lex.europa.eu/. Very likely Google Translate has a sort of artificially intelligent mechanism intended to assist in translating crawled web pages autonomously. A similar behavior can be found in a report posted at Reddit[4] (thanks to my brother YaBa) where a user tried to translate TODOTODOOOTODOTODOTODOTODO… and got TripAdvisor bietet Ihnen kostenlose und einfache… instead.

Generating patterns

When testing a program, part of given input string was leaked from memory but with a different encoding. For example, the input AAAAAAAA produce the string ƨƘ䅁䅁䅁䅁y. After dissecting the output, it was possible to conclude this string was Unicode escaped. Each two bytes were grouped and presented as one Unicode codepoint, i.e., \u01a8\u0198\u4141\u4141\u4141\u4141\u0079.

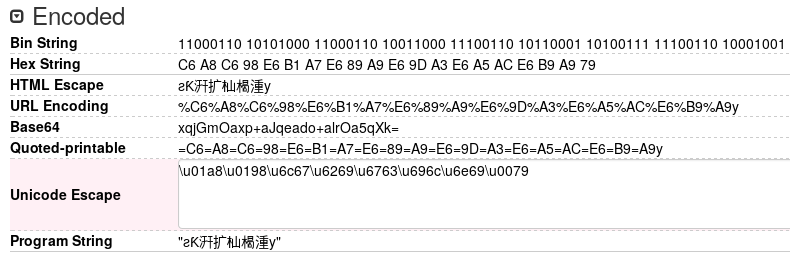

The next step was using a specific keyword as input to produce a reasonable string. Providing the word glibcglibcglibc as input we can observe the returned value being the following (dencode.com):

This particular string was created by the hexadecimal sequence \x01\xa8\x01\x98\x6c\x67\x62\x69\x67\x63\x69\x6c\x6e\x69\x00\x79 equivalent to ��lgbigcilniy in ASCII (notice the endianness).

At this moment we have a method to build custom strings with specific words that could perhaps guide our search. In other words, providing a concrete string will possibly make our search less dumb even though it is composed mostly by “random” characters. Google is able to extract and process information contained in such strings as observed while using translation feature.

Results

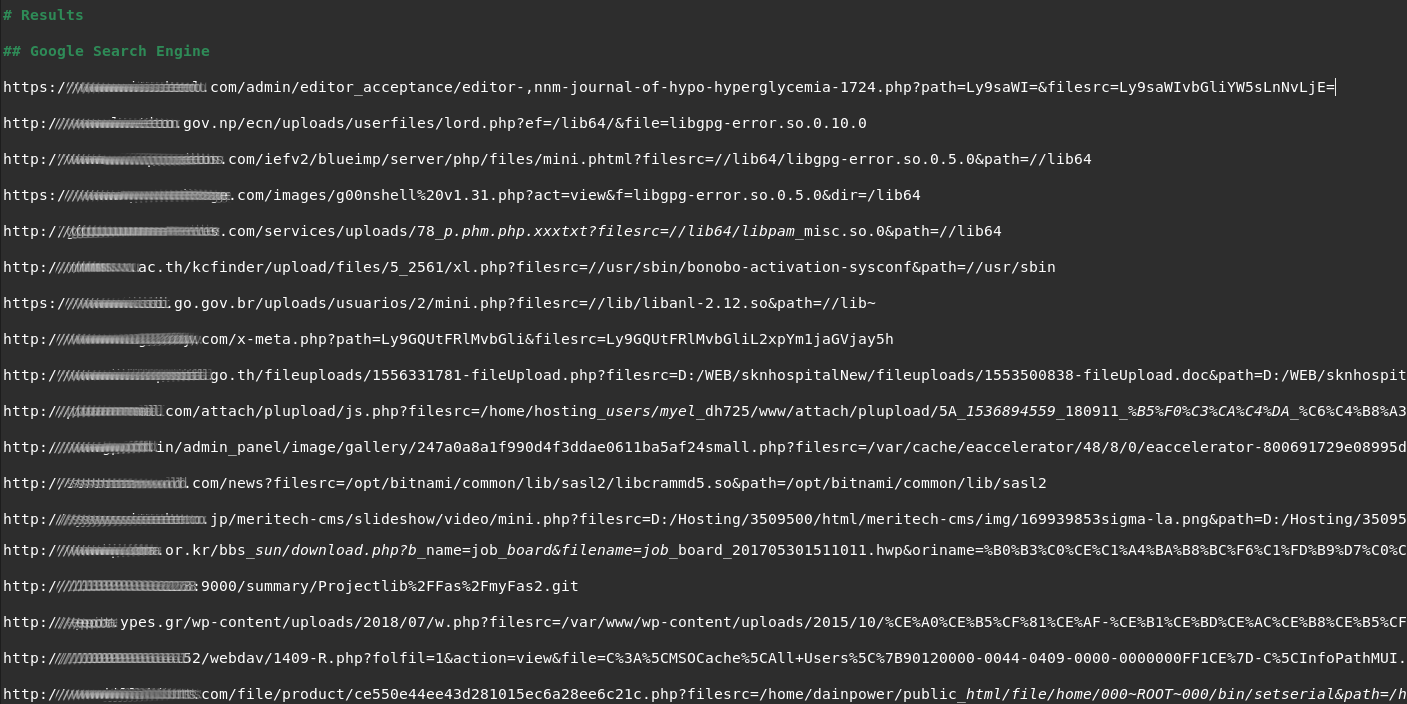

By searching the previously generated string we can expect libc related stuff to be displayed in results (e.g. .so libraries).

Adding a typical keyword commonly used in webshells parameters filesrc (intended to load local files) to our custom search term will potentially show results of uploaded backdoors on compromised servers that are not directly displayed when searching more generic terms.

First result contains malicious PHP code that was likely uploaded by a cyber attacker and includes a simple interface displaying system information, a file upload function and enable editing files located at a writeable directory.

Image demonstrating the view after being redirected from Google search engine. The current loaded file (libdl.so.2) holds a pattern that match our search term.

It is unknown how and why this particular URL was included into Google dataset. Probably due to Google’s optimization when selecting relevant results to display. Search engines effectiveness tend to be more precise now than some years ago[5]. Nevertheless, this does not explain why such URL is indexed with a .so file loaded. From my personal experience, it’s hard to believe an attacker has interest in opening a .so file over this text interface for two reasons:

- First, it does not contain valuable information (considering this scenario);

- Second, editing and saving a non-text file in web shell interface would corrupt it, leading to malfunction of programs requiring this shared object to run.

This may lead to interesting insights about how/if Google is caching compromised systems, on purpose (or not).

Conclusion

Constructing creative search expressions can lead to interesting results. This may be useful while gathering information during a pentest reconnaissance and enumeration phase but on the other side it could also be convenient to detect threats.

It is now evident that Google search engine do recognize when a user searches for terms similar to strings we presented. We started by observing translations from CJK characters sequences to a URL. Then, using a first example we got multiple results of binary files. By crafting a custom string, we were able to find system libraries included in web pages via uploaded malicious scripts, thus proving Google has indexed numerous URLs likewise.

The final outcome of gathering Google results using various string manipulation techniques as described above is the following.

References

- [1] Long, J. (2005). Using Google as a Security Testing Tool [Slides]. https://www.blackhat.com/presentations/bh-europe-05/BH_EU_05-Long.pdf

- [2] Long, J. (2004). You found that on Google? [Slides]. https://www.blackhat.com/presentations/bh-asia-04/bh-jp-04-pdfs/bh-jp-04-long.pdf

- [3] Mider, D. (2019). The Internet Data Collection with the Google Hacking Tool – White, Grey or Black Open-Source Intelligence? - Przegląd * Bezpieczeństwa Wewnętrznego - Volume 11, Issue 20 - CEJSH - Yadda. http://cejsh.icm.edu.pl/cejsh/element/bwmeta1.element.desklight-2fc6e5dc-a980-4da0-b53b-d7adcb536c20

- [4] Reddit (2017). https://www.reddit.com/r/ProgrammerHumor/comments/6po5n2/i_might_have_found_a_bug_in_google_translate/

- [5] Lewandowski, D. (2015). The Retrieval Effectiveness of Web Search Engines: Considering Results Descriptions. http://arxiv.org/abs/1511.05800

Appendix

- Strings used (base64 encoded):

- 7ISB5KKD7ICB6KGQ77yP65iR6JOS55el7qaj75O/77+H5JCk4KCBw6nkt7Lvv78=

- 5rGn5omp5p2j5qWs5rmpIGZpbGVzcmM=

Archived pages in Wayback Machine (slightly different results):

http://web.archive.org/web/20200425134936/https://www.google.com/search?source=hp&ei=5D-kXuvzN-OflwS8rrPgCg&q=%EC%84%81%E4%A2%83%EC%80%81%E8%A1%90%EF%BC%8F%EB%98%91%E8%93%92%E7%97%A5%EE%A6%A3%EF%93%BF%EF%BF%87%E4%90%A4%E0%A0%81%C3%A9%E4%B7%B2%EF%BF%BF&oq=%EC%84%81%E4%A2%83%EC%80%81%E8%A1%90%EF%BC%8F%EB%98%91%E8%93%92%E7%97%A5%EE%A6%A3%EF%93%BF%EF%BF%87%E4%90%A4%E0%A0%81%C3%A9%E4%B7%B2%EF%BF%BF&gs_lcp=CgZwc3ktYWIQA1BQWFBg7wFoAHAAeACAAQCIAQCSAQCYAQCgAQKgAQGqAQdnd3Mtd2l6&sclient=psy-ab&ved=0ahUKEwjr9cr_24PpAhXjz4UKHTzXDKwQ4dUDCAY&uact=5

http://web.archive.org/web/20200425135059/https://www.google.com/search?source=hp&ei=N0CkXuLxGfKPlwSGnJvgDw&q=%E6%B1%A7%E6%89%A9%E6%9D%A3%E6%A5%AC%E6%B9%A9+filesrc&oq=%E6%B1%A7%E6%89%A9%E6%9D%A3%E6%A5%AC%E6%B9%A9+filesrc&gs_lcp=CgZwc3ktYWIQA1DSAVjSAWC9AmgAcAB4AIABAIgBAJIBAJgBAKABAqABAaoBB2d3cy13aXo&sclient=psy-ab&ved=0ahUKEwii6fam3IPpAhXyx4UKHQbOBvwQ4dUDCAY&uact=5